Plane Waves in a Tenuous Plasma, Dispersion

The general introduction to dispersion you will find in Griffiths section 9.5. The content on plasmas you will not find in Griffiths. It was taken from lecture notes of Steve Boughn for Physics 204 at Princeton in 1983 (It turns out plasmas behave the same way now as they did 40 years ago). His original notes are here.

Where we are

For the last two weeks we’ve been putting together everything we have gathered about Maxwell’s equations in vacuum and in media to understand the propagation of electromagnetic waves in vacuum and in media.

Today we’re talking about what happens to an EM wave in a particular kind of conductor. A plasma. We’ll use this example as a case study for talking about dispersion. Dispersion is where waves of different frequencies travel at different velocities.

Where we’re going

What happens next is:

- Then we need to go back to potentials, particularly vector potentials, so that we can understand deferred potentials, so that we can understand how radiation occurs. (We’ve talked about electromagnetic waves, but you’ll notice we haven’t talked about how we generate them at all. We ve just assumed they’re there and tried to understand their properties. In this very last section of the course, we need to generate them.

What we did last time.

Intensity you measure in a lab for an EM wave (time averaged Poynting vector):

\[I \equiv <S> = \frac{1}{2} \epsilon v E_0^2.\]Lots of relationships between energy density, momentum, and poynting vectors. \(\vec{g} = \frac{1}{c^2} \vec{S} = \epsilon_0(\vec{E} \times \vec{B})\)

(Momentum density in a medium is controversial so I wrote that one in a vacuum - see Griffiths note at the bottom of page 402.)

\[\vec{S} = cu\hat{k}\](I wrote that one in a vacuum, but it’s equally true in media as long as you replace \(c\) with \(v\).)

So And we have this general equation for energy density:

\[u = \frac{1}{2} \left(\epsilon_0E^2 + \frac{1}{\mu_0}B^2\right)\]and we realized that the energy contributions from the E and B fields are equivalent.

Dispersion

The good news is that you really have all the machinery you need already to do this. You’ve been studying how the velocity of waves depend on the permittivity \(\epsilon\), the permeability \(\mu\), and the conductivity \(\sigma\). All of those depend upon frequency.

You also already know the effects of this.

A raindrop bends blue light more

sharply than red, so you get a rainbow.

A prism does the same thing, so you get a rainbow.

The phenomenon is called dispersion, and a medium that does it is called dispersive.

The mathematics of it depends on something you learned in PHY213. The phase velocity of a single wave is

\[v = \frac{\omega}{k}\]We’ve been using that for a couple weeks now.

In 213 we learned that if you have a packet of waves, they travel at the group velocity

\[v_g = \frac{d\omega}{dk}\]So if you want to know how fast a wave packet travels, you need to know how \(\omega\) is related to \(k\) for that medium. That’s called the dispersion relation.

Let’s figure out what it is for a plasma.

Why are we concentrating on a plasma?

We’re doing this for several reasons.

- Plasmas are cool and are found all over the universe.

- The physics of them is pretty simple (because by definition they are diffuse, so you don’t need fluid mechanics - not many collisions) so we can derive the dispersion relation.

- They’re really just a nice example of a conductor. We haven’t gotten to play around with complex conductivity \(\sigma\) yet, and we’re about to.

- Every signal we detect in astrophysics has to travel through a plasma to get to us, so we really need to understand the effects of the plasma on the waves.

Great, what’s a plasma?

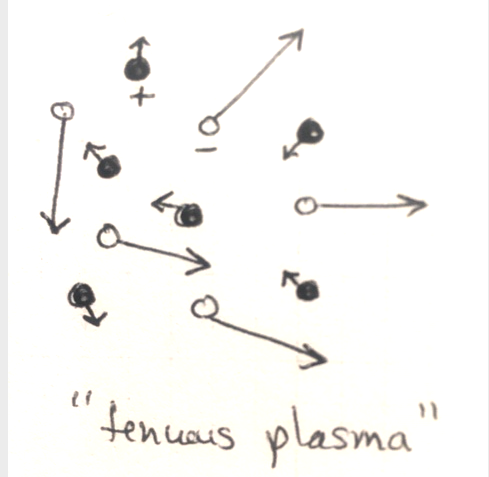

A plasma is really just a gas of electrons and positrons. They “don’t collide much” which for us means they don’t collide on the order of one oscillation of an EM wave. The protons are so massive compared to the electrons, that we only consider the electrons.

]

]

You can see why I call this a conductor, right? The electrons are free!

**Step 1: Get the velocity of the electrons as it related to the frequency of the EM wave

The force on the electrons is

\[\vec{F} = -e(\vec{E} + \vec{v}\times\vec{B})\]Let’s compare the magnitudes of the electric and magnetic forces. (Why? Because we want to ignore the magnetic field and make our life easier!!!)

\[\frac{e\vec{E}}{e\vec{v}\times\vec{B}} \approx \frac{E}{vB}\]but you know \(E/B = c\) so \(E/vB\) is \(c/v\). So as long as \(v<<c\) the magnetic force is negligible.

So now we can write:

\[\vec{F} = -e\vec{E}\]or (using Newton’s 2nd law)

\[m_e\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} = -e\vec{E}\]For a plane wave:

\[\vec{E} = \vec{E}_0(z)e^{-i\omega t}\](I just stuck the \(e^{kz}\) into the \(\vec{E}_0\))

So now, on your own integrate that to get an expression for \(\vec{v}\). You don’t care about the limits of integration. You just want an expression for v the derivative of which gives you the right expression for E. So you can do it as an indefinite integral.

\[\vec{v} = -\frac{e}{m_e}\vec{E}_0\int e^{-i\omega t} dt\] \[\vec{v} = \frac{e}{i\omega m_e}\vec{E}_0\]The next thing we need to do is get a conductivity out of this.

(Your (fourth?) homework problem involves doing the same thing I’m

about to do but with a different expression for velocity.)

We want a conductivity because then we can use expressions we already know

for how waves propagate in media with \(\sigma\). I’ll give away part of

the punchline here, and say that waves can travel unattenuated under certain

conditions in this plasma (which is good because otherwise we’d detect nothing

astrophysically).

The equation above is telling you the relationship between the electric field and the velocity of the electrons. What does the \(i\) mean? It means that the electrons are lagging behind the E-field by \(\pi/2\). It’s a driven oscilator system just like we studied in PHY213.

To get a conductivity we need a relationship between J and E. Whatever that constant of proportionality is will give us \(\sigma\).

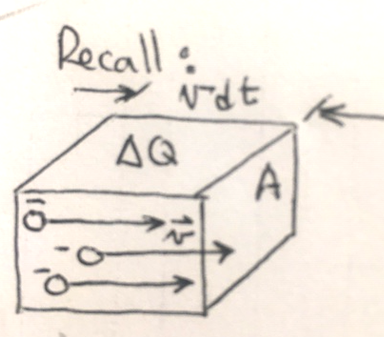

Consider a little rectangular section of this plasma. Cross-sectional area A and length \(vdt\) (the distance the electron can travel in a time \(dt\). The amount of charge in the rectangular box is \(dQ\).

]

]

If \(n_0\) is the number density of electrons then \(dQ = -en_0Avdt\). Then the current is

\[dQ/dt = -en_0Av\]and

\[J = \frac{1}{A} \frac{dQ}{dt} = -en_0v\]and we can use our expression for velocity:

\[\vec{J} = -en_0\vec{v} = \frac{ie^2n_0}{\omega m_e}\vec{E}\](I got rid of the minus sign by bringing the \(i\) into the numerator.)

And the conductivity is: (because \(J=\sigma E\) <- that’s actually the definition of conductivity)

\[\sigma = \frac{ie^2n_0}{\omega m_e}\]And again, it’s imaginary because the velocity is out of phase with the E. The dependence upon \(n_0\) and \(m_e\) is reassuring. Those are both in the positions I would expect them to be in.

And now we can use this conductivity in our expression for complex \(k\).

\[k^2 = \mu_0\epsilon_0\omega^2\left(1 + \frac{i\sigma}{\epsilon_0\omega}\right)\]Here’s another assignment for you: Take this expression for k, substitute in our sigma, and find what’s called the plasma frequency \(\omega_p\) by making your solutions look like this:

\[k^2 = \frac{\omega^2}{c^2}\left(1 - \frac{\omega_p^2}{\omega^2}\right)\]Ans:

\[\omega_p^2 \equiv \frac{n_0e^2}{\epsilon_0m_e}\]So now, in your groups, using that expression for \(k^2\). Discuss under what circumstances (what conditions on \(\omega\) the wave will propagate unattenuated.)

Ans: when \(\omega > \omega_p\). Then you get

\[k = \frac{w}{c}\left(1 - \frac{\omega_p^2}{\omega^2}\right)^{1/2}\]and the \(k\) is real.

Next in your groups: Find \(v_g\) for this wave. Ans:

\[v_g = \frac{c}{\sqrt{1 + \frac{\omega_p^2}{\omega^2 - \omega_p^2}}}\]Next in your groups: Start problem #5 on the homework using this expression.